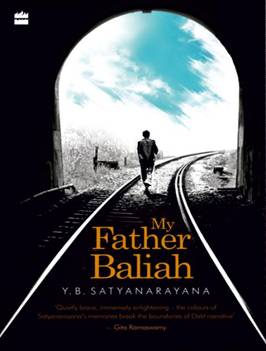

Though not commensurate with the huge population, Creative Writing by Indians has become common. Still, finding an English book of a Telugu writer, among the piles of foreign ones interspersed here and there, with Indian writings, gives a refreshing breather. More so, with ‘My Father Baliah’; a recently released memoir of Y.B. Satyanarayana by Harper Collins. A rare one of the genre of experiential dalit writing in English.

The book is a lucid and brief rendering of the lives of 4 generations beginning with Narsaiah, his son Narsaiah, his son Baliah and one of his sons Y.B.Satyanarayana. In addition to being a ‘Madiga’ by caste, one of the last rung of the social ladder of varna, the senior Narsaiah, as a landless labour, is a subject of Nizam’s oppressive revenue system in the form of the upper caste landlords. The junior Narsaiah, distraught over the death of his endearing wife owing to cholera, unwittingly, bids goodbye to his village along with his son. With the help of his maternal uncles, he joins the Nizam’s railways. While employment breaks the hold of feudalism, living in quarters in towns, subdues the caste discrimination too. Baliah grows enduring stepmother’s treatment; all by himself becomes a semi-literate, takes up a job in the railways and marries. Midway, Baliah seems to go astray with over drinking and living with a lady. He, however, stands his ground, takes in the lady as his wife, and together they breed almost a score of children, of whom our protagonist too is one. Baliah, though not educated, finds education and through it a job in the railways, only way out of the social and financial predicament. The children too imbibe this.

What are more striking in the narration are the discipline and the passion to get educated, that Baliah instills in the children, despite the appalling conditions of housing, food and clothing. Simply stated but touching is the familial love among the members. Finally, Y.B. Satyanarayana and two of his brothers earn doctorates in their respective subjects and the tale ends. The gripping nature of the theme, a sprinkle of words of Telangana dialect, several unknown or rather forgotten details of names and local practices – all together make it an exponential read. Given the familiar vocabulary and expressions used, it is an inspirational work for children – to know the value of academics and the inhumanness of caste.

Single minded in their devotion to wriggle out of oppressions of caste and poverty and uplift themselves to an independent life of dignity, none of these real life characters seem to be affected by the political movements that overwhelmed their respective periods – the Telangana armed struggle, the movements for a separate state and categorization of scheduled castes for equitable distribution of opportunities under reservations. The writer, as it appears from a few sentences, is influenced by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. He appears to have taken to Buddhism too. Of these however, nothing is stated in the book. May be, they are reserved for another one, which is obviously welcome.